1992年の春、金子淳は一人のアーティストが手掛けたものとしてはおそらく史上最大規模の粘土プロジェクトを開始した。オマハ・プロジェクト』から10年近くが経ち、金子は再びカリフォルニア州フリーモントにあるミッション・クレイ・プロダクツ社の巨大な工業用窯を利用できるようになった。ミッション・クレイの窯は通常、テラコッタ製の下水パイプを製造するために使われていたが、工場のマネージャーで自身も陶芸家であるブライアン・ヴァンセルは、ミッション・クレイのアーティスト・レジデンス・プログラムの一環として、金子を巨大な蜂の巣窯に招待した。金子は、2つの窯と2年半の歳月をかけて、25個のダンゴを丁寧に作ることにした。

金子はまず、このプロジェクトに関連する工学と化学の基本的な要素をすべて研究するのに数年を費やし、20冊以上のノートを埋め尽くした。粘土ミキサー、40トンの乾燥粘土体、足場、特別に設計されたフォークリフトなど、オマハからの機材と物資を2台のセミトラックで運んだ。金子と3人のアシスタントは5月から8月まで精力的に働き、1日平均500ポンドの粘土を混ぜ、5フィートから11.5フィートの大きさの金子のダンゴを丁寧に作り上げた。

乾燥が進むにつれて、ダンゴの底にひびが入り、巨大な壁の重圧に耐えきれなくなったのだ。戸惑いながらも、金子と彼のアシスタントたちは6つのダンゴをすべて破壊し、乾燥した粘土を何トンもハンマーで叩きつけて固め直した。その後、彼らは再び始めた。

金子にとって、フリーモントのプロジェクトは実験と学習であり、ひび割れの解決策を見つけようと決意していた。このような規模のセラミックは誰もやったことがないため、どうすればいいのか誰もアドバイスしてくれないのだ。「専門家たちからの情報は、私の役には立たなかった。

ある日、アシスタントたちがスレッジハンマーでダンゴを倒しているとき、金子は日本にいる友人の鈴木五郎と電話で話した。鈴木は疑問は理解していたが、金子のような一枚岩の形を作ったことがなく、問題を解決する方法がわからなかった。しかし、彼は金子に言った。「日本で急須を作るとき、トリミングの前に底を少し叩いて逆ドームにするよね。そうすると1個もなくならないんだ。この逆ドームを作ると、クッションができて、収縮ムラの緊張から逃れられるんです" 金子はこのアドバイスを2度目のダンゴ作りに取り入れた。

金子によれば、"1回目の震災で多くのことを学んだので、すべてのものをどのように動かせばいいのかがわかったので、もっと早くできるようになった "という。 ダンゴの2度目の製作は成功し、18ヶ月の乾燥期間を経て、最初のビスク焼成の準備が整った。その後、釉薬掛けと2度目の焼成が行われ、1994年9月、大成功と祝賀のうちに窯が開かれた。

溶接工程, ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツ

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツでダンゴを造るジュン

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツでダンゴを造るジュン

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツでダンゴを造るジュン

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

ミッション・クレイ製品

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツのダンゴ

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

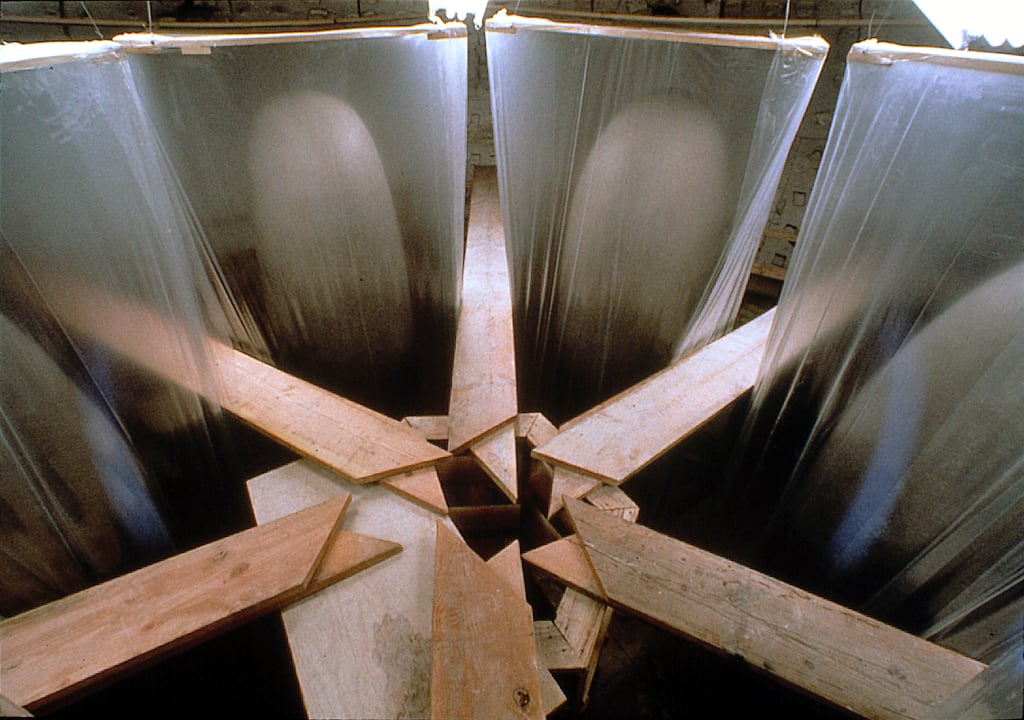

乾燥工程、ビニールテント内のダンゴ。ミッション・クレイ製品

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツ アシスタント

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真金子淳スタジオ

ミッション・クレイ社の窯の中のダンゴ

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真金子淳スタジオ

ミッション・クレイ社の窯の中のダンゴ

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツの窯の中でダンゴと一緒にいるジュンとアシスタントたち

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真金子淳スタジオ

ジュンとアシスタント・グレーズ、ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツ

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

ジュンとアシスタント・グレーズ、ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツ

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

ジュン・グレージング, ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツ

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

ミッション・クレイ製品

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真金子淳スタジオ

ミッション・クレイ製品

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真金子淳スタジオ

トラックに積まれ、ミッション・クレイ・プロダクツを出発するダンゴ

1994

米国カリフォルニア州フリーモント

写真畠山崇

無題, 団子

1995

79×48×24インチの手造り、釉薬のかかった陶器。 米国カリフォルニア州サンノゼ、サンノゼ・レパートリー・プラザに設置。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1994

125×63.25×36インチ。 米国ネバダ州オマハ、リー&ジュン・カネコ財団蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1994

123.25×63.5×36.25インチ。 米国ネバダ州オマハ、リー&ジュン・カネコ財団蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1994

123×64×37.75インチ。 米国ネバダ州オマハ、リー&ジュン・カネコ財団蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1994

121.75×61.5×38インチ。 米国ネバダ州オマハ、リー&ジュン・カネコ財団蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1994

123.75×60.5×38.25インチ。 米国ネバダ州オマハ、リー&ジュン・カネコ財団蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

90×54×22インチ、手作業で作られ、釉薬がかけられた陶器。 米国カリフォルニア州ウェスト・サクラメント市所蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

手作業で作られ、釉薬がかけられた陶器、88 x 52 x 22インチ。 米国ネバダ州オマハ、ローリッツェン・ガーデン蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

80×62×23インチ。 米国ミネソタ州ミネアポリス、ミネソタ大学フレデリック・R・ワイズマン美術館蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

92×54×27インチの手造り、釉薬のかかった陶器。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

手作業で作られ、釉薬がかけられた陶器、高さ約96インチ。 米国カリフォルニア州ウェスト・サクラメント市所蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

手作業で作られ、釉薬がかけられた陶器。 個人蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

83×61×24インチ、手作りで釉薬をかけた陶器。 米国カリフォルニア州サンノゼ、サンノゼ・レパートリー・プラザに設置。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

81×52×25インチ。 個人蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

手作業で作られ、釉薬がかけられた陶器。 個人蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

84×52×24インチの手造り、釉薬のかかった陶器。 米国カリフォルニア州パサディナのウエスタン・アセット・プラザに設置。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

87×53×24インチ。 米国ネバダ州オマハ、リー&ジュン・カネコ財団蔵。

写真ディルク・バッカー

無題, 団子

1995

79×48×24インチの手造り、釉薬のかかった陶器。

写真ディルク・バッカー